What led you to your career in crop Physiology and agriculture?

I was teaching sixth grade and I loved it, but I was telling my students that you could do anything you wanted to do, and you could make a difference. World hunger was an issue (and still is) particularly in Africa in the ’70s, and I became interested in it. I found out that, as a land grant university, Ohio State had money for research in agriculture. So, I got my master’s at Ohio State. Then I was offered a job in California with Dow, which had an agricultural division, but I really wanted to continue on.

I went to meetings of our professional society, American Society of Agronomy. I met someone from the University of Arkansas who said they were looking to recruit, particularly Blacks because they had none —most of the schools didn’t. I met with them and was recruited, so I did my Ph.D. at the University of Arkansas.

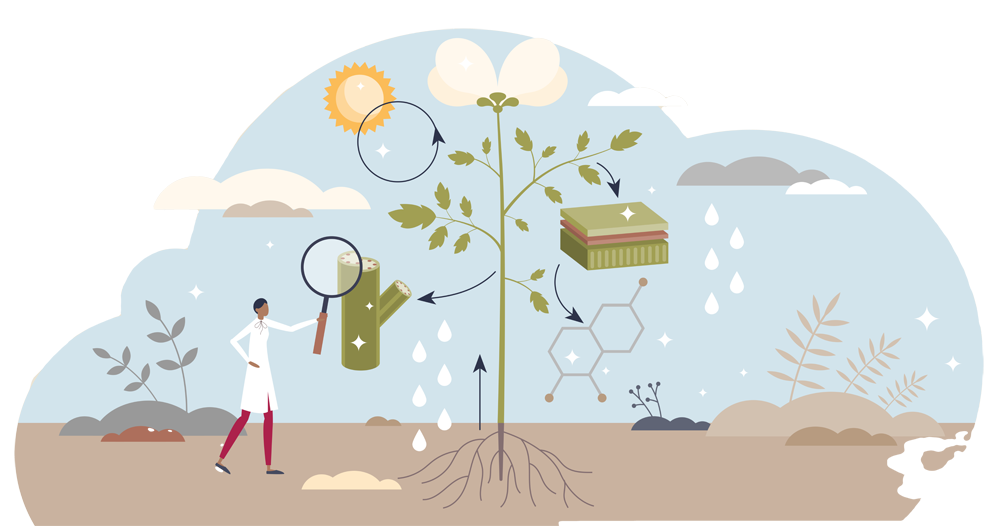

What does your research entail?

When I was at Ohio State, the associate dean of the department asked me, “Do you want to study horticulture or agronomy?” I didn’t know what either one was, so I said I want to study whatever is going to teach me how to grow the foods that people eat. He said agronomy, so I studied agronomy (the science of soil management and crop production) at Ohio State.

I wanted to study more about the issues that plants have: How do they grow better? What governs the growth of plants? That’s physiology, which is what I studied at the University of Arkansas. When I came to Michigan State University, I taught crop production, introduction to crop science, and crop physiology.

In terms of research, I worked with soybeans, dry beans, kidney beans, Navy beans, and those kinds of beans. I looked at a drought resistance and cover crops and was able to have some involvement with Mexico in a research program, some with Malawi and students from other parts of Africa, and so forth.

Why is your research important in today’s era of climate change?

Even before the almost-crisis that we’re in right now, areas would have periodic episodes of drought. When that happens, the plant doesn’t grow and develop. It may die. You don’t get the yield. In some parts of the world, it was even more often than it was happening here. Now it’s happening more often everywhere with extreme temperatures, excessive moisture, and all of those different issues.

We now have 8 billion people, and it has been projected to reach 9 or 10 billion by 2050. We need to feed those people. I’m a Trekkie, but I don’t expect to get the Starship Enterprise or any other ship anytime soon that’s taking us to different places. So, we’ve got to be able to feed ourselves here and now and it’s got to be nutritious food. With climate change that’s going to be even harder than it has been.

It was already going to be hard enough trying to increase yield, but with having serious drought at times, excess rain, tornadoes, it will be even more difficult. So, my discipline is extremely important, and the unfortunate part is that most people don’t know anything about it.

When most people think of agriculture, they think of farming. That’s fine, except that in the U.S. less than 1% of the people feed the rest of us and grow additional food to export. Plus, we also need the people in the other countries producing enough food to sustain themselves.

That means that this discipline needs to look at: what do we need for the crops to grow, for soils to be fertile? There are also issues with fertilizer and fertilizer run-off, with pesticides and pesticide run-off, diseases and insects. We need to be able to deal with all that and grow food. So, this discipline is extremely important.

What challenges have you faced as a black woman in your field?

When I first I came to Michigan State, I was the first female in our department and the first person of color in our department. There are times when you say something, and they don’t hear it. I am a very assertive person, and I became even more assertive. I think over time people knew that when Eunice speaks, I’m going to tell you what I think and I’m going to be very assertive about that.

But when I had one-on-one interviews with people, someone said to me, “Are you applying for this job because you want to be the first woman and the first Black here?” Now that’s not a legal question. But I smiled and I looked at him and I said, “I applied because you have a job and I need a job.”

I didn’t say it to be offensive but to me it was a common-sense question. You apply when people have a job, and you need a job.

I can’t remember if it was the same man, but someone later said to me, “I should have known we were going to have to hire a woman sometime because we have these women students.”

People would say things that they didn’t realize were offensive, and some of these people were men I came to like, in fact many of them. But I did have to work to change things.

There were there was a course in another college, Women in Science, and the people had asked me to put up flyers in our department. A person in my department took them down and said, “We don’t want our students taking this course.”

There was hostility towards women in science and so you had to be a strong person. But I didn’t come into agriculture for people to like me. I came into it for a purpose. I grew up in the 1950s, and the hostility towards Blacks was not so different — I would hear my parents talk. You couldn’t be a frail, weepy person. You can’t run me away.

We ended up founding an organization called Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences, and it’s still going strong. We had 1,000 members at our last national meeting. There are many professionals of color that are operating in universities, government, industry, and non-profits who have come through this organization and been nurtured.

The students at MSU were the impetus. It’s been amazing for me to see the growth and the national impact, and from the beginning it was students of color saying, we want to know who else is out there and we want to recruit.

But it always has been open to everyone and nurtured everyone. We have Caucasian students, we have African Americans, Latinx, Native Americans, Asian Americans. We also have high school chapters now, which build a pipeline.

Why is it important to include minority scientists and scholars in conversations in your discipline?

In every discipline we need all of our human capital. Intelligence is not in any one race.

I gave a three-minute presentation on this recently. I started with Lue Gim Gong. In the 1890s in Florida, there was a terrible freeze, and they pretty much lost the citrus crop. This young man who came here as an immigrant by himself at age 12 from China, did research and came up with varieties that were that were freeze tolerant. He’s called the “Citrus Wizard of Florida” and most people have never heard of him.

Then I mentioned Ynes Mexia. In the 1920s, she started college when she was 51. She collected 145,000 species, 600 that had never collected before, and over 60 of them have her name in them somehow. Suppose we didn’t have her.

Then I mentioned an African American woman named Gladys West. In the ’70s and ’80s, she did some mapping with the stratosphere and the Earth’s gravitational pull and other things that led to foundation of the GPS that we have in cars and phones. Suppose we didn’t have her.

Then I mentioned a lady named Robin Wall Kimmerer, who is working with Native American concepts of plants and nature and what we’ve lost, what we need to regain, and how that we can use that.

Intelligence is not scarce and it’s not in any one race, nor any one gender. We need different viewpoints, different ways of looking at things, different ways of thinking, so that we challenge each other in a positive way.

There’s a saying that if you and your partner always agree, one of you is unnecessary. It’s not my saying I but I love it. We need constructive, positive criticism and thinking and we need everybody’s ideas.

What have you done to support and encourage minority scientists in your field?

We have a grant that’s finishing up now from the National Science Foundation to recruit more students into seven disciplines, including agronomy.

Many people don’t know of the need for science. We don’t have enough people coming into these disciplines — people of any color. The grant is for everyone, but I’m proud to say that we had 34% diversity and we’ve been very successful with 82% of our students graduating in four years or less. We spent a lot of time nurturing, encouraging, meeting monthly with the students, and bringing in speakers. We built in money for them to do internships, study abroad, and go to professional meetings.

We also go into high schools, especially three high schools in our lower socioeconomic district once a month with hands-on activities. And our college also has some summer programs. If a student finds something that interests them, we want to be able to build upon that.

I’ve gone to an Afrocentric school and talked to their first, second, third, and fourth graders about seed science and they did a garden this summer. My goal is to create a pipeline because even though I’m retiring, I would like this program to continue in high schools.

How has your lifelong commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion been meaningful to you?

As an African American woman, it could not be otherwise to know from whence we’ve come and the challenges we’ve overcome, even in my lifetime. I want to know history and we have to know it. Unfortunately, it isn’t taught in school; you can’t teach history with just one race or another.

I know the struggles that my parents went through. I know that any struggles that I’ve had have been miniscule compared to what they had, and theirs were miniscule compared to the people before them. And that I know that it was not accidental. There were laws that

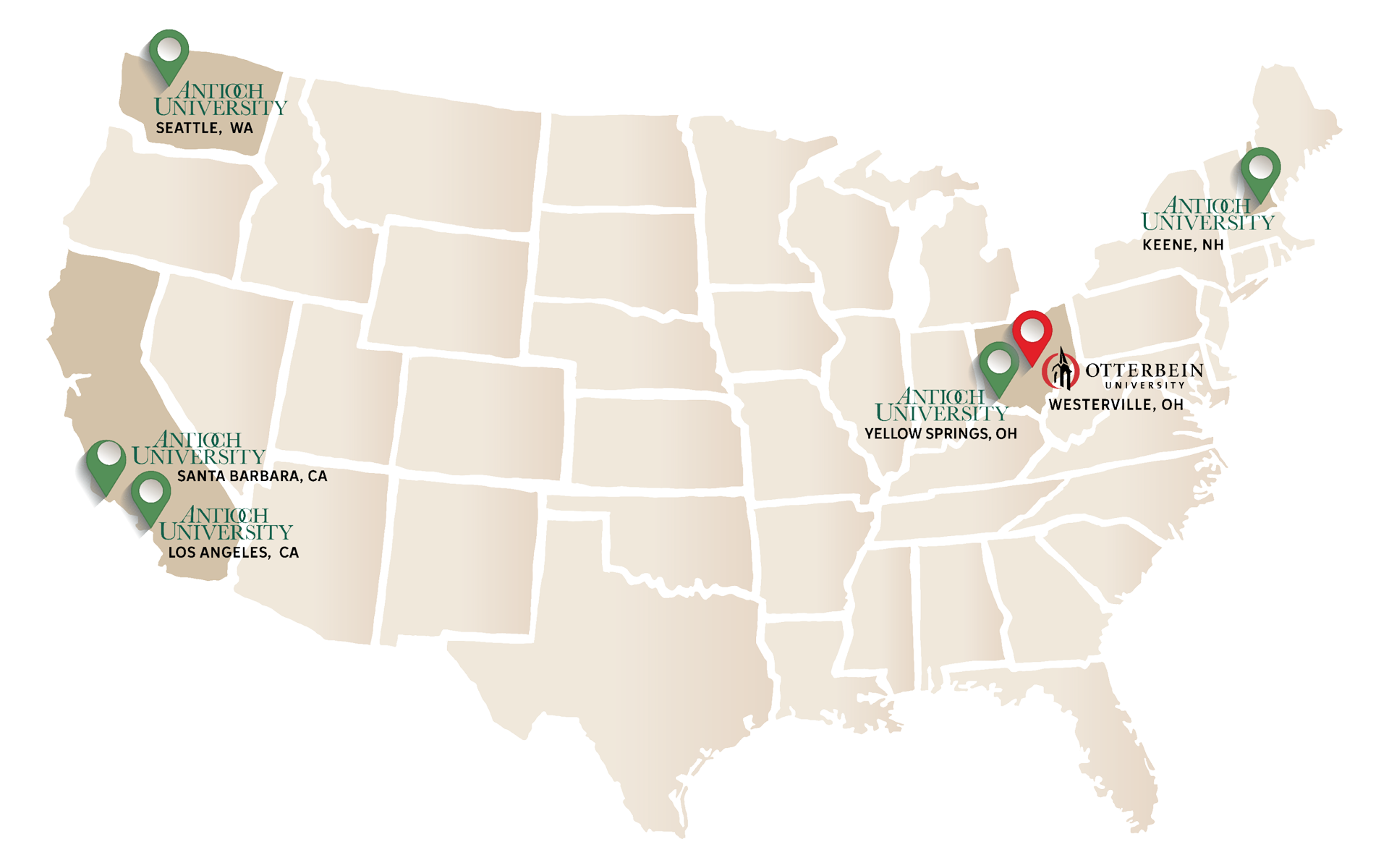

Otterbein Welcomes New Director of Annual Giving

Otterbein Welcomes New Director of Annual Giving

You can email or call me, and I’ll help you explore all the options available. Want to read more first? Let me know that, too, and I can give you the facts you need to help you decide. When you make a gift at Otterbein, you make a difference. That’s a fact. Reach me by email at kbonte@otterbein.edu or by phone at 614-823-2707.

You can email or call me, and I’ll help you explore all the options available. Want to read more first? Let me know that, too, and I can give you the facts you need to help you decide. When you make a gift at Otterbein, you make a difference. That’s a fact. Reach me by email at kbonte@otterbein.edu or by phone at 614-823-2707.

Bachelor of Science in Nursing:

Bachelor of Science in Nursing:

College of Distinction:

College of Distinction: It is in the top three regional universities in Ohio and 20th in the Midwest. Additionally, Otterbein was recognized on the following lists: Best Colleges for Veterans (ranked sixth, top 4%); Best Undergraduate Teaching (ranked 12th, top 7%); Best Value Schools (jumped 11 places to rank 26th); and A+ School for B Students. View the entire survey at

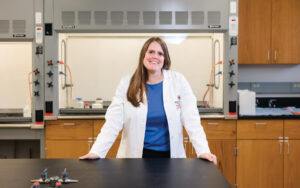

It is in the top three regional universities in Ohio and 20th in the Midwest. Additionally, Otterbein was recognized on the following lists: Best Colleges for Veterans (ranked sixth, top 4%); Best Undergraduate Teaching (ranked 12th, top 7%); Best Value Schools (jumped 11 places to rank 26th); and A+ School for B Students. View the entire survey at  The awards committee cited Esson’s implementation and invention of evidence-based pedagogies; generation of student interest via real-world applications of chemistry; advancement of chemistry teaching though research and publication; mentorship of early-career chemistry educators; and leadership on campus and in local chemistry education organizations.

The awards committee cited Esson’s implementation and invention of evidence-based pedagogies; generation of student interest via real-world applications of chemistry; advancement of chemistry teaching though research and publication; mentorship of early-career chemistry educators; and leadership on campus and in local chemistry education organizations.

MISES

MISES

EUNICE FOSTER, Ph.D., graduated from Otterbein with a degree in Elementary Education in 1970. After teaching at Main Street Elementary School in Columbus for four years, she was called to a new career. Now a crop physiologist at Michigan State University, Foster has broken glass ceilings as the first African American and the first female associate dean in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. She works to lift others up as a founding member of the National Society for Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences (MANRRS) — an organization she emphasizes is inclusive of everyone — which now has 65 chapters in 35 states.

EUNICE FOSTER, Ph.D., graduated from Otterbein with a degree in Elementary Education in 1970. After teaching at Main Street Elementary School in Columbus for four years, she was called to a new career. Now a crop physiologist at Michigan State University, Foster has broken glass ceilings as the first African American and the first female associate dean in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. She works to lift others up as a founding member of the National Society for Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences (MANRRS) — an organization she emphasizes is inclusive of everyone — which now has 65 chapters in 35 states.